Introduction

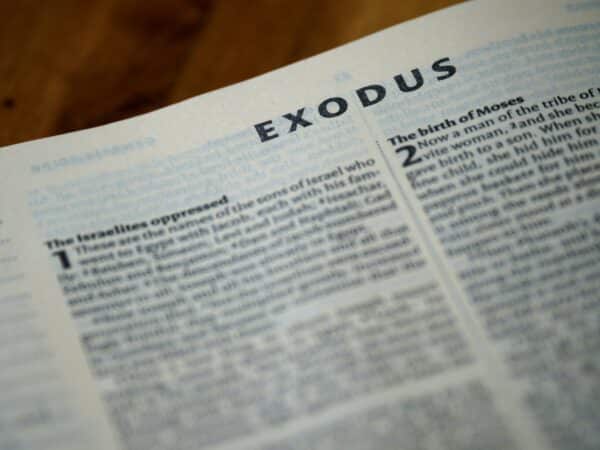

“And the LORD said: ‘I have surely seen the oppression of My people who are in Egypt, and have heard their cry because of their taskmasters, for I know their sorrows. So I have come down to deliver them out of the hand of the Egyptians, and to bring them up from that land to a good and large land, to a land flowing with milk and honey, to the place of the Canaanites and the Hittites and the Amorites and the Perizzites and the Hivites and the Jebusites. Now therefore, behold, the cry of the children of Israel has come to Me, and I have also seen the oppression with which the Egyptians oppress them. Come now, therefore, and I will send you to Pharaoh that you may bring My people, the children of Israel, out of Egypt.’” (Exodus 3:7–10)

This is the beginning of God’s commissioning of Moses to go and be His messenger to deliver the people of Israel from Egyptian slavery.

As we read in the Exodus narrative, Moses is very reluctant at first to answer this call—this is not really his personal choice. The LORD is the one God; He chose to deliver His people. This was not going to be an easy task, nor a short mission.

Knowing the stubbornness of Pharaoh, king of Egypt, God devised a grand spectacle to lead the children of Israel out of slavery with “a mighty hand and an outstretched arm.”

These signs and wonders are famously known as “The Ten Plagues.”

So, what’s up with these plagues—and why did God specifically devise each one of them?

When we read the biblical narrative, we discover that the ‘why’ of the Ten Plagues actually has several layers and reasons.

Because Pharaoh Will not Let Israel Go Easily

In Exodus 3:19–22, we learn that God already knows Pharaoh won’t let the children of Israel go easily—not even by a mighty hand. That’s why He will strike Egypt with ALL His wonders, and only then will Pharaoh let them go. He also describes how these plagues will cause the Egyptians to be willing to be “plundered” by the Israelites.

So that the Egyptians Shall Know That He is the LORD

In Exodus 7:3–5, God tells Moses that He will multiply His signs and wonders in Egypt, so that,

“the Egyptians shall know that I am the LORD, when I stretch out My hand on Egypt and bring out the children of Israel from among them.”

So that His Name May Be Declared in all the Earth

By the time the seventh plague comes around, God declares that through the plagues, He will teach Pharaoh and the Egyptians that there is none like Him in all the earth, and that it was for this very purpose that He raised Pharaoh up:

“that I may show My power in you, and that My name may be declared in all the earth.”

Before the eighth plague, God shares another crucial reason with Moses:

To Tell His Wonders to the Next Generation

“Now the LORD said to Moses, ‘Go in to Pharaoh; for I have hardened his heart and the hearts of his servants, that I may show these signs of Mine before him, and that you may tell in the hearing of your son and your son’s son the mighty things I have done in Egypt, and My signs which I have done among them, that you may know that I am the LORD.’” (Exodus 10:1-2)

Here, God says that He is multiplying the plagues so that we would tell our children and grandchildren about the mighty things He did in Egypt—the signs and wonders He performed there—which we still do to this day during the Passover Seder, by means of the Passover Haggadah.

The final reason we’ll present here is found in Exodus 12:12. This fascinating verse, which appears toward the end of this entire spectacle, reveals that there’s more to the plagues than what first meets the eye:

The 10 Plagues: Judgment Against all the gods of Egypt

“For I will pass through the land of Egypt on that night, and will strike all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, both man and beast; and against all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgment: I am the LORD.” (Exodus 12:12)

Here, God declares that He is executing judgment against ALL the gods of Egypt.

So how did He do that?

One widely held belief is that He did so through the 10 plagues, humiliating the Egyptian gods and proving that He alone is God.

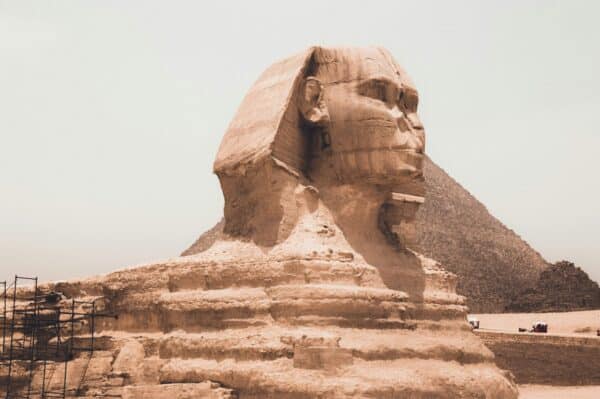

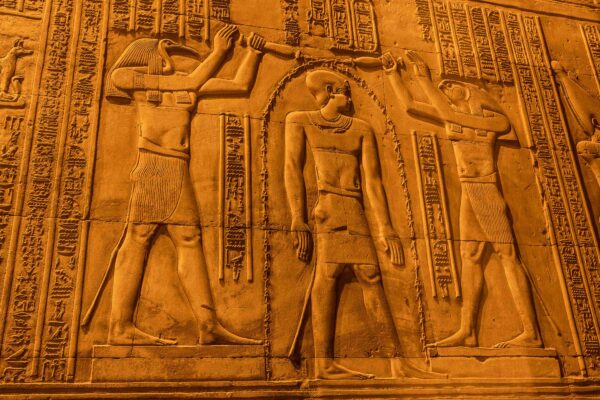

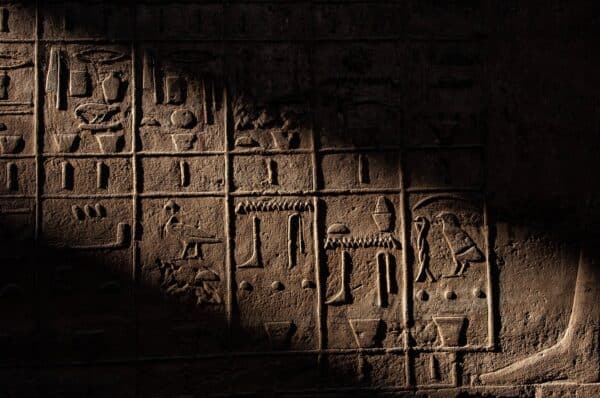

At the time, Egypt stood as the world’s dominant empire, boasting one of the most ancient and intricate religious systems on Earth. Experts believe that Egypt had a pantheon of up to 2000 gods and goddesses. Through the plagues, God confronted and dismantled an entire spiritual and political order.

The first judgment on Egypt's gods, and in particular against its ‘snake gods,’ actually begins before the first plague. Moses casts down his staff before Pharaoh and it becomes a snake, and as Pharaoh’s magicians do the same with their staffs, Moses’s staff/snake swallows theirs.

In Egyptian mythology, Nehebkau—the original snake god—was a powerful protective deity, often depicted on ivory rods and widely worshiped in the mid-second millennium B.C.E. According to the Coffin Texts (c. 2100 B.C.E.), he gained power over magic by swallowing seven cobras.

The Hebrew snake swallowing the Egyptian snakes in the name of the God of Israel was a striking display of supremacy.

Egyptians believed Nehebkau played a central role in the afterlife, reuniting the dead with their souls—making it significant that this miracle came before the fatal plagues.

This act also challenged other snake deities—especially Wadjet, the cobra goddess revered as the protector of Lower Egypt, where the land of Goshen, home to the Israelites, was located.

When Moses’s snake consumed the others, the message was unmistakable: It was not Wadjet or Pharaoh, but the God of Israel who reigned supreme in Lower Egypt.

Before any plague struck, God delivered a direct, symbolic blow to Egypt’s gods and its ruler.

Now to the first plague:

Water Turned into Blood (מכת דם)

Turning the Nile to blood was a direct strike against Osiris, Egypt’s god of fertility and agriculture, whose “bloodstream” was believed to be the Nile itself. As the Nile’s chief deity, Osiris symbolized life—so when God turned the river into literal blood, it became a source of death and suffering.

This miracle also challenged other Nile-related gods: Khnum (source of the Nile), Hapi (flooding), and Sopdet (fertility through floodwaters), as well as Nu, Naunet, Tefnut, Nehet-Weret, and the fish-goddess Hatmehit.

Although Pharaoh’s magicians replicated the plague, they couldn’t reverse it. Even deities like Taweret, the “goddess of Pure Water,” failed to cleanse the Nile or the rest of the water that had turned to blood.

The second Plague: Frogs (מכת צפרדע)

Heqet, the best-known Egyptian frog goddess, symbolized childbirth, midwifery, and resurrection—key themes in the Israelite story. Pharaoh had once ordered Israelite baby boys to be killed by midwives and drowned in the Nile river (Exodus 1:15–22), and now, in the second plague, frogs—symbols of those very themes—poured back out of the Nile. The irony in this was likely not unnoticed by Pharaoh.

The third Plague: Dust Turned into Lice (מכת כינים)

Whether the creatures mentioned in this plague were truly what we know as lice today is contested. There are many different translations and interpretations of the Hebrew word. The word does seem to indicate some kind of animal that bites or digs into the skin.

The ground came alive with parasites—among others, an attack on Geb, Egypt’s earth god. It also directly targeted Egypt’s priests, who obsessed over ritual purity and even removed their eyebrows and eyelashes to avoid lice. This plague was a nightmare for them—and they were helpless against it.

It was during this plague that the magicians gave up, telling Pharaoh, “This is the finger of God.” (Exodus 8:19)

The Fourth Plague: Swarms (מכת ערוב)

Flies and beetles held symbolic value in ancient Egypt. They decorated ritual objects, and elite soldiers wore the “Order of the Golden Fly” to represent bravery and persistence.

That admiration likely faded after the fourth plague.

The Hebrew word used simply means “swarms.” Based on the Greek Septuagint, most scholars identify these as dogflies—painful, blood-sucking insects, known to spread deadly diseases.

Psalm 78:45 says the swarms “devoured” the Egyptians—an image of severe suffering.

Fly- and insect-related deities included Wadjet, Iusaaset, and Khepri (with a beetle head). Bees were believed to come from Ra’s tears, and certain wasps were part of the pharaoh’s royal titles.

Ironically, because these swarms represent Egyptian persistence and determination, the plague broke Pharaoh’s resolve—he agreed to release the Israelites, though he changed his mind once the swarms vanished.

The Fifth Plague: The Death of the Livestock (מכת דבר)

This plague struck at many Egyptian animal gods, especially cattle deities—the most revered animals in their pantheon. Chief among them was Hathor, cow-goddess, daughter of Ra, and “mother of the pharaoh,” who was often depicted as a bull. Art even shows pharaohs suckling from her udder. (This is the same cow goddess that is often referenced in connection to the sin of the golden calf.)

Another major figure was the Apis bull, a divine ‘son of Hathor’ and living symbol of Pharaoh. Only one Apis bull could exist at a time; when it died, it was mourned, mummified, and buried.

Verse 6 of chapter 9 implies that the Apis bull died among all other livestock of Egypt during this plague—a symbolic hit to Pharaoh himself.

The Egyptians viewed Israelite livestock practices as a blasphemous “abomination,” so watching their own cattle die while Israel’s remained untouched was deeply troubling. In apparent unbelief, Pharaoh even sent messengers to confirm it.

The Sixth Plague: Boils (מכת שחין)

This plague crippled Egypt, the narrative notes that even the magicians couldn’t stand upright.

The outbreak of boils challenged key Egyptian deities: Sekhmet (epidemics and healing), Thoth (medical knowledge), Isis and Nephthys (healing and health). It also struck at Egypt’s famed doctors, celebrated for their medical skills since 2600 B.C.E., including Imhotep, later deified as a god of medicine.

Moses initiated the plague by tossing furnace ash into the air. The word used refers to a brick-kiln, which is powerfully symbolic, as Israelite slaves had suffered brutal labor making bricks. Now, in poetic justice, the Egyptians were covered in boils from the very symbol of that oppression.

The Seventh Plague: Hail (& Fire) (מכת ברד)

This plague devastated everything and everyone not under solid shelter. Nut, the sky-goddess meant to shield the land, was absent—as was Shu, god of calm skies. The gods tied to animals and crops (Set, Isis, Osiris) were nowhere to be found either.

The fire in the storm struck at Egyptian views of the afterlife. Being burned was the worst fate—no body meant no mummification, and thus, no afterlife. Even hail-damaged corpses posed a problem, as Egyptians believed the body had to remain intact. Making it worse, flax—a key crop for mummy wrappings—was destroyed.

This time, Pharaoh grew desperate. He admitted his sin and acknowledged Israel’s God. Why now?

In Egyptian belief, Pharaoh upheld Maat—cosmic order—and was responsible for keeping chaos at bay. But with deafening thunder, hail, fire, and lightning tearing through Egypt, that order was gone. The land was in total chaos—and everyone knew Pharaoh had lost control.

Yet despite his servants' pleading, he changed his mind once again, refusing to let God’s people go.

The Eighth Plague: Locusts (מכת ארבה)

Locust swarms are common in the region, but this plague was unlike anything Egypt had ever seen.

It wiped out every remaining crop—wheat and spelt that had survived the hail—leaving nothing behind.

This was a blow to major agricultural deities like Neper, Nepri, Heneb, Renenutet, and also Isis and Set, who were believed to protect Egypt’s harvests.

With no crops left, famine loomed. Pharaoh repented and agreed to let Israel go. Moses accepted, but… Pharaoh changed his mind again.

Now, judgment would fall on Egypt’s greatest god…

The Ninth Plague: Darkness (מכת חושך)

Ra, Egypt’s supreme sun god—also worshiped as Re, Amon-Ra, Atum, or Aten—was considered more powerful than all other gods. So central was his worship that Pharaoh Akhenaten once banned the worship of any other deity.

The ninth plague directly targeted Ra. As darkness fell, Egypt’s greatest god was shown to be powerless.

It was also a warning to Pharaoh, seen as the “son of the sun.” Meanwhile, in Goshen, the Israelites enjoyed light (Exodus 10:23).

The first nine plagues built up to the 10th plague, and thus could be categorized separately. Interestingly, Egyptian religion revered the number nine—seen in enneads, or nine-god groupings. The most famous was the Great Ennead of Heliopolis, led by Atum and including gods impacted in earlier plagues. Sometimes, Horus—the son of Isis and Osiris—was added as a tenth. All of this led to what came next: the final and most devastating plague.

The Tenth Plague: The Death of the Firstborn (מכת בכורות)

The tenth and final plague struck all at once—Pharaoh, commoners, even animals—and shattered every god tied to them. In a culture that revered firstborns, this was a devastating blow. The narrative notes that no Egyptian household was spared.

Pharaoh and his family were seen as demigods—divine beings above mortal suffering. Yet in this plague, God struck Egypt’s most “untouchable” figure: Pharaoh’s own son, the child-god, considered part of the divine pantheon. This loss was more crippling than Pharaoh’s own death.

After this, Egypt was broken. The Israelites were finally freed. Egyptians, humiliated and desperate, “thrust” them out, even ‘paying’ them to leave.

With the final plague fulfilled, Israel departed in joy, and Egypt was left in ruin. God had accomplished exactly what He intended.

The Distinction Between God’s People and His Enemies

One last thing that is relevant to point out is that it was only by the time the fourth plague hit, that God announced that He will make a distinction between the Egyptians and His people from then forward.

This brings us to the interesting conclusion that the first three plagues hit everyone, Egyptians and Israelites alike, until God decided that from that point onward He would set His people apart, protect them, and only strike His enemies.

Beyond the similarities between the plagues in Exodus and the judgments in Revelation, we find a particularly interesting parallel to this principle of distinction in the final book of the Bible.

The interpretation of the book of Revelation can be contentious, but that’s not our focus right now. We simply want to highlight the parallel: after allowing a measure of suffering, God sets His people apart, in this case by marking them.

In Revelation 7:3 we read the command of the Angel coming from the east to the other four angels who are about to strike the world:

“Do not harm the earth, the sea, or the trees till we have sealed the servants of our God on their foreheads.”

And in Revelation 9:4 we read about yet another terrible plague of locust-like creatures that only harm those not marked as the servants of God:

“They were commanded not to harm the grass of the earth, or any green thing, or any tree, but only those men who do not have the seal of God on their foreheads.”

Conclusion

Several lessons can be learned from the 10 plagues and judgments on the Egyptian gods:

First of all, our God, the God of Israel, is the only God and there is no other. He is high and exalted far above all other so-called ‘God’s and He is all powerful.

Secondly, we are reminded of the importance of teaching the next generation–our children–about the great works of God and what He has done for us.

Thirdly, we learn that God cares about His people and makes a distinction between those who are His and the rest of humanity. Though His children suffer at times and experience hardship, His love and faithfulness is unwavering. He is with us and protects us as a whole, as His people.

May this story of the Exodus of our fathers and the remembrance of His signs and wonders in Egypt never cease to inspire us, increase our faith and give us hope for the future, knowing that God cares about His people!

(*credit: some of the historical information is gleaned from the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology)

Thank you for this teaching. I appreciate Netivyah’s ministry. I have visited there during fall feasts of 2017. And will always remember the wonderful experience.

May the the Lord bless you and God’s people. My prayers are with you for peace and protection and the return of the remaining hostages. ✝️

Shalom Julie!

Thank you for your kind words and for standing with us in prayer!

God bless you

Thank you so much for this lesson, you’ve explained in more detail than I’ve heard before! I appreciate and am very thankful for the Netivyah bible instruction ministry!

Love and Blessings,

your sister Juli

Shalom Juli,

Thank you so much for your kind words and feedback!

Happy Passover