What is Pesach?

Pesach, or Passover, is one of the most significant and widely observed Jewish/biblical festivals. Every year on the anniversary of 'the Exodus,' in the spring, at the full moon of the first month of the biblical year (Aviv/Nisan), the children of Israel commemorate the miraculous Exodus from Egypt, which marked their liberation from slavery and journey towards becoming a nation under God. Pesach is celebrated for seven days in Israel and eight days in the Jewish diaspora, beginning on the 15th of Nisan. The holiday serves as a powerful reminder of God’s faithfulness, and covenant with His people, and as a “blueprint” of God’s overarching salvation plan for humanity throughout history.

Historical Background

Origins

The origins of Pesach date back to the 13th century BCE, when the Israelites were delivered by God from their enslavement in Egypt. This enslavement in Egypt did not happen by chance; rather, it was prophesied centuries prior in the book of Genesis:

“Then He (God) said to Abram: ‘Know certainly that your descendants will be strangers in a land that is not theirs, and will serve them, and they will afflict them four hundred years. And also the nation whom they serve I will judge; afterward they shall come out with great possessions. Now as for you, you shall go to your fathers in peace; you shall be buried at a good old age. But in the fourth generation they shall return here, for the iniquity of the Amorites is not yet complete.’” (Genesis 15: 13-16)

Many years later, when Israel and his sons settled in Egypt during the famine, they remembered this promise and prophecy. In faith, Joseph commanded his brothers before his passing:

“And Joseph said to his brethren, ‘I am dying; but God will surely visit you, and bring you out of this land to the land of which He swore to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob.’ Then Joseph took an oath from the children of Israel, saying, ‘God will surely visit you, and you shall carry up my bones from here.’” (Genesis 50:24-25)

Generations after, the children of Israel did not forget the God of their fathers, the God of Abraham.

The book of Exodus (chapter 2: 23b-25) recounts:

“Then the children of Israel groaned because of the bondage, and they cried out; and their cry came up to God because of the bondage. So God heard their groaning, and God remembered His covenant with Abraham, with Isaac, and with Jacob. And God looked upon the children of Israel, and God acknowledged them.”

Note that it does not say to whom the children of Israel cried out, and yet it is reasonable to believe that they cried out to the God of their fathers. This belief is derived from Numbers 1, based on the names of the tribal leaders of Israel, which contain special meanings that not only give insight into the collective memory of the God of their fathers, but also into their identity in God and relationship with Him.

After the Pharaoh had ordered all Israelite boys to be killed, one Israelite mother hid her newborn son for 3 months in their home. When she could no longer hide him, she put him in a basket among the reeds by the Nile river banks. When Pharaoh's daughter came to bathe in the river, she noticed the basket with the baby boy, saved the child, adopted him, and called his name Moshe (Moses).

When Moses was 40 years old, he came to the defense of one of the Hebrew slaves who was being abused by an Egyptian, and killed the Egyptian while doing so. When this deed became known, Moses fled and lived for 40 years in 'exile' in the land of Midian.

From there, God called Moses and sent him as His chosen leader to demand Israel's release from Pharaoh, but Pharaoh repeatedly refused, leading to the Ten Plagues.

The final and most devastating plague was the death of the firstborn. To protect themselves, the Israelites were commanded to sacrifice a lamb and smear its blood on their doorposts so that the Angel of Death would "pass over" their homes, sparing their firstborn while striking down the firstborn of Egypt. This event led to Pharaoh finally relenting and allowing the Israelites to leave Egypt. Pesach is named after this act of divine protection. The root of the word 'Pesach' is the Hebrew word for 'to pass over,' referencing the Angel of Death passing over the houses of the Israelites and sparing them.

Learn more about the Hebrew Names in the book of Numbers

Learn more about The 10 Plagues & the Judgements on Egypts gods

Agricultural Significance

In addition to its historical significance, Pesach is tied to the agricultural cycle. It occurs in the spring, coinciding with the barley harvest in Israel. In ancient times, this harvest was celebrated by bringing the first sheaf of barley (the Omer) as an offering to the Temple in Jerusalem, kicking off the “counting of the ‘Omer’” that continues until the feast of Shavuot.

Pesach is one of the 3 annual festivals connected to the harvest, when every Israelite male was commanded to come up to Jerusalem to celebrate the feast.

Learn more about the counting of the Omer.

Observance Throughout History

The observance of the Passover was instituted in the Torah and has had both good and bad times in biblical history. We read in Joshua 5:10-11,

“Now the children of Israel camped in Gilgal, and kept the Passover on the fourteenth day of the month at twilight on the plains of Jericho. And they ate of the produce of the land on the day after the Passover, unleavened bread and parched grain, on the very same day.”

After this positive start in the book of Joshua, there were multiple, long periods when the Passover was not fully celebrated by the children of Israel.

After a long season marked by many ups and, more often, downs, we come to 2 Chronicles 30:26, where we read about the great 'Passover Revival' led by King Hezekiah:

“So there was great joy in Jerusalem, for since the time of Solomon the son of David, king of Israel, there had been nothing like this in Jerusalem.”

About 100 years later, under King Josiah, a similar but even more magnificent celebration took place, as recorded in 2 Chronicles 35:18,

“There had been no Passover kept in Israel like that since the days of Samuel the prophet; and none of the kings of Israel had kept such a Passover as Josiah kept, with the priests and the Levites, all Judah and Israel who were present, and the inhabitants of Jerusalem.”

Although the second temple period had its difficult times (for example, the story of the Maccabees), it was generally a very religious and observant period where the Passover was celebrated until the temple’s destruction in 70 CE.

Although, for obvious reasons, some aspects of the observance of Passover have changed, the destruction of the temple did not prevent our people from celebrating and keeping the Passover. Our collective remembrance of God’s redemption of our people continues even to this day.

Biblical Background

Pesach is extensively mentioned in the Torah and its observance is commanded multiple times:

Exodus 12:1-51 describes the original institution of the Passover, detailing the lamb’s sacrifice, the meal, and the marking of doorposts with blood.

Exodus 13:1-16 reminds the people of the importance of the removal of all leaven as well as the redemption of the firstborn, which are connected to the Exodus and emphasize the importance of teaching one’s children and passing down this collective memory.

Learn more about teaching one's children and the collective memory.

Leviticus 23:4-8 gives instructions for observing Pesach and the Feast of Unleavened Bread.

Numbers 9:1-14 gives an account of the people of Israel celebrating the Passover and a way for those unable to observe Pesach at its proper time to celebrate it a month later (called 'Pesach Sheni,' meaning 'Second Passover').

Deuteronomy 16:1-8 retells the command to observe Pesach, emphasizing its connection to God’s deliverance.

Key biblical narratives and themes associated with Pesach include:

- The ten plagues, culminating in the death of the Egyptian firstborns.

Learn more about The 10 Plagues & the Judgements on Egypts gods - The hurried departure from Egypt, which is why leavened bread (chametz) is forbidden.

Learn about the significance of removing Chametz from one's heart and home - The parting of the Red Sea, ultimate salvation of the Israelites from Egyptian oppression, and the song of Moses.

- The command to remember and retell the story of the Exodus for future generations.

Learn about the importance of teaching one’s children and the collective memory - Yeshua’s celebration of the Passover with His disciples and the inauguration of the New Covenant.

Curious to learn more? Check out these articles:

Yeshua as the Lamb of God

The Passover Seder

How is Pesach observed?

The holiday of Passover begins with what is called 'Yom Tov,' literally meaning, 'good day.' Yom Tov is a high point of the festival when work is prohibited. Its laws are similar in nature to those of the weekly Shabbat, though slightly different.

The first Yom Tov of Passover is followed by several days of 'Chol HaMoed,' which literally means, 'weekday of the festival.' These semi-festive, intermediate days exist in both Passover and Sukkot, after which the feast concludes with another 'Yom Tov.'

Cleaning out Chametz (Leaven)

The observance of Pesach actually begins before the holiday starts, though an intensive, deep clean of one’s house, to clear out all leaven according to what God commanded:

“Unleavened bread shall be eaten seven days. And no leavened bread shall be seen among you, nor shall leaven be seen among you in all your quarters.” (Exodus 13:7)

On the night before the Passover there is a last 'ceremonial search' of leaven and on the next morning before the holiday, all the leftover leaven is burned outside to 'purge' all the leaven from among us.

To learn more about the significance of removing chametz from one's heart and home click here.

The Passover Seder

The most important tradition of Pesach is the Seder, held on the first night (and also on the second night in the diaspora). Families and communities gather to recount the Exodus story using the Haggadah, a structured guide that includes readings, prayers, songs, and symbolic foods.

The most important parts of the Passover Seder are:

Eating Matza and Bitter Herbs – Eating matzah and bitter herbs helps us to remember the bitter slavery, as it is written: “...with unleavened bread and with bitter herbs they shall eat it.” (Exodus 12:8)

Reciting the Passover Haggadah – This tradition of reciting the Haggadah helps us to fulfill the commandment of recounting the story of the Exodus and the Passover to our children. It actively involves the children in several ways, such as by giving them four traditional questions to ask and letting them search for the “Afikoman.” (Traditionally, three pieces of matzah are placed at the middle of the Seder table, and the middle one is called the Afikoman. Relatively early in the Seder, the Afikomen is broken into two pieces. The bigger piece is then wrapped in a napkin and hidden somewhere in the house. After the meal, the kids are sent to hunt for the hidden Afikoman, and whoever finds it gets a special reward.)

Learn more about the meaning of the Afikoman in this video series by Joseph Shulam.

Drinking four cups of wine – We drink four cups of wine, each of which has its own title and represents one of the stages of the Exodus:

1) The First Cup: 'The Cup of Sanctification'

This cup ushers in the holiday with 'Kiddush' ('Sanctification' over a cup of wine for Shabbat and holidays). It embodies God’s statement that says: “I will take you out from their burdens….” This first step is traditionally understood as salvation from harsh labor, which began with the onset of the plagues.

2) The Second Cup: 'The Cup of Deliverance'

This cup is blessed and taken right after the 'Maggid' in the Haggadah, which is the recounting of the details of the Exodus. The second cup embodies God’s statement, “I will rescue you from their bondage….” This second step is traditionally understood as salvation from servitude.

3) The Third Cup: 'The Cup of Redemption'

This cup is poured right before reciting 'Birkat HaMazon' (the prayer of thanksgiving after meals) and drunk right after completing it.

The third cup embodies God’s statement that says: “I will redeem you with an outstretched arm….” This third step is traditionally understood in light of the parting of the Red Sea, after which the children of Israel felt completely redeemed, without fear of their former oppressor recapturing them.

This is the very cup that Yeshua took after the meal: “Then He took the cup, and gave thanks, and gave it to them, saying, ‘Drink from it, all of you. For this is My blood of the new covenant, which is shed for many for the remission of sins.’” (Matthew 26:27-28)

4) The Fourth Cup: 'The Cup of Praise'

This cup follows the singing of the 'Hallel' (meaning: 'Praise'), which are Psalms 113-118. The fourth cup embodies God’s statement: “I will take you to Me for a people….” This fourth step is traditionally understood as the 'becoming a nation' at Mount Sinai and as a vision of the days of the Messiah.

Learn more about the Passover Seder.

Learn more about remembrance and teaching one's children.

Celebrate Pesach at home using our "How to Celebrate Pesach at Home Guide"

The Offering of the “Omer” (“Sheaf/Measure”)

Due to the absence of the temple, this is currently not observed, yet relevant for those who personally wish to commemorate it.

In Leviticus 23:9-14, we read about the first 'Omer,' the sheaf/measure of grain from the new harvest (the word 'Omer' can mean both a sheaf of barley and it is also a measurement for grain). The Omer is an offering of firstfruits, brought together with a lamb, a meal, and drink offering on the day after the Shabbat.

This offering starts off 'Sfirat HaOmer' (meaning 'The counting of the Omer'). In 1 Corinthians 15:20, Yeshua is called the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep, probably because He most likely rose from the dead on this very day.

Sfirat HaOmer (The Counting of the Omer)

As mentioned above, on the second evening of Passover (the day after the Shabbat) we start counting the Omer as commanded in Leviticus 23:15-16:

“And you shall count for yourselves from the day after the Sabbath, from the day that you brought the sheaf of the wave offering: seven Sabbaths shall be completed. Count fifty days to the day after the seventh Sabbath; then you shall offer a new grain offering to the LORD.”

The counting of the Omer begins with the feast of Pesach, though its observance continues beyond the festivities of Pesach and culminate in the feast of Shavuot (also known as 'Feast of Weeks' or 'Pentecost'). This is traditionally a time of spiritual preparation and anticipation for the agricultural feast of Shavuot, which is associated with the divine revelation and giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai and the giving of the Holy Spirit on Mount Zion.

Learn more about the counting of the Omer!

Chol HaMoed (The Weekday of the Festival)

Unlike the first and seventh days of Passover, which are called a 'holy convocation' when work is prohibited, work is not forbidden during the intermediate days of the feast (called 'Chol HaMoed'), unless the intermediate day falls on the weekly Shabbat. However, we still try to work as little as possible during Chol HaMoed days.

In Jewish law, there is a whole list regarding what is allowed and what is not during these days. Besides a list of many work-related activities that are either allowed, restricted or forbidden, it is interesting to note that no weddings are held during those days, fasting is prohibited, and mourning practices are changed. Many families see these days as a perfect opportunity for family outings.

The special commandments for the festival are equally observed on Chol HaMoed, like the prohibition of eating chametz (leaven) and the command to be joyous and celebrate.

The Reading of Song of Songs

The Book of Song of Songs is traditionally read on the eve of Passover after the Seder.

There are several reasons why this book is read; for example, Pharaoh is mentioned in the book and its content is symbolic of Israel's four exiles and redemption from each one.

The main and traditional way of understanding this tradition is that Song of Songs represents the love story between God and the children of Israel, who, through the Exodus, made a covenant with Him and became betrothed to Him.

Special Blessings Prayers for Pesach

Special prayers and blessings are prayed, sung, and recited throughout the holiday of Passover. In addition to those found in the Passover Haggadah, there are several prayers recited during the rest of the holiday as well.

Beyond the blessings surrounding the counting of the Omer, there are special additions to the regular daily prayers that are included throughout the weekdays of the holiday—especially in the Amidah (standing prayer) and the Birkat HaMazon (the thanksgiving prayer after meals).

According to tradition, the parting of the Red Sea took place on the seventh day of Passover. Because of this, the Song of Moses is a central theme in the prayers and readings on that day.

It is also a widespread Jewish custom to recite Hallel (Psalms 113–118), with certain omissions, on the weekdays of the holiday.

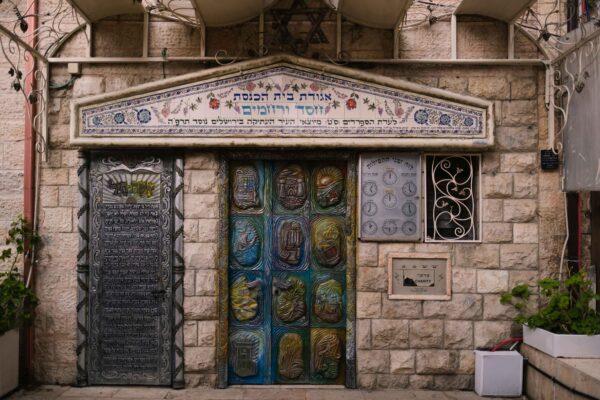

Additionally, special Torah readings take place in synagogues throughout the week of Pesach.

Traditional Foods for Pesach

The Seder Plate

Matzah (Unleavened Bread) – known as the 'bread of affliction,' is eaten throughout Pesach as a reminder of the humble and hurried nature of the Exodus. As is written in Deuteronomy 16:3:

“You shall eat no leavened bread with it; seven days you shall eat unleavened bread with it, that is, the bread of affliction (for you came out of the land of Egypt in haste), that you may remember the day in which you came out of the land of Egypt all the days of your life.”

It is also the very bread that we encounter in Matthew chapter 26 that Yeshua takes, blesses and breaks and as he gives it to His disciples says:

“Take, eat; this is My body.”

Maror and Chazeret (Bitter Herbs) – These remind us of the bitterness of slavery of our forefathers in Egypt.

“…and with bitter herbs they shall eat it.” (Exodus 12:8)

Zeroa (Shankbone) – This piece of roasted meat is to remind us of the Passover Lamb that was sacrificed on the eve of the Exodus and annually in the Temple, in the afternoon before Pesach.

While some use a forearm of a lamb, most people simply use a chicken leg or neck since the symbolism matters more than the matter itself in this case.

This “Shankbone” serves as a reminder only and is not eaten.

Beitzah (Egg) – It serves as a reminder of the pre-holiday offering that was brought in the days of the Temple. Others connect it to the remembrance and mourning for the destruction of the Temple. It is eaten as part of the main meal during the Seder.

Charoset (Paste) – This paste, based on sweet apples, walnuts, and red wine, represents the mortar and brick that was used by the children of Israel when they toiled as slaves for Pharaoh. During the Seder, one dips the Maror into this paste and then puts it in a “Matzah Sandwich” together with the Maror. The remaining charoset is usually eaten spread on Matzah.

Karpas (Vegetable) – We usually use parsley for this, called "karpas" in Hebrew, though some people use onion or boiled potato. When rearranging the letters of the word 'Karpas' in Hebrew, we can form the word 'Perech,' which means 'harshness,' and is connected to the harsh labor of our slavery in Egypt. We can also form the word for the letter 'Samech' which has the numerical value of 60, connected to the 60 myriads (600.000) – the number of Jewish slaves aged 20 years and up during the time of the Exodus.

After Kiddush and the traditional washing of hands, this Karpas is dipped in saltwater and eaten after the recitation of a blessing. The saltwater represents the tears of the Israelites during their slavery.

Cultural Dishes

Besides the traditional elements on the Seder plate, the foods that are traditionally eaten in Jewish communities around the world vary, from slow cooked lamb (lamb tzimmes) to braised beef brisket, to different vegetable and fish dishes like the Jewish Moroccan Chraime.

Click here to see Joseph Shulam's Roasted Leg of Lamb Recipe.

And then of course, there are the dishes connecting with the theme of the holiday, the dishes that are made with Matzah like Kneidlach Soup (Matzah Ball Soup), Matzah Brei, Matzah crusted fried chicken, or Mina, a Sephardic dish where matzah is stacked with meat or vegetables.

Click here to see the Gliks' Kneidlach Recipe.

Beyond the culturally known Matzah dishes, you can find all kinds of new Matzah foods and inventions, like sea salt Matzah chocolate crackers, Matzah Pancakes, or Matzah Pizza… the possibilities are endless for any creative Matzah-loving mind.

To see Sam's Matzah-Pancakes recipe click here.

Pesach in Israel and Around the World

In Israel, Pesach is a national holiday. Schools are closed and many businesses also close on Chol HaMoed (Weekday of the Festival) in addition to the sacred first and seventh days. Since most school breaks start a whole week before Pesach, many families use this opportunity to travel. Many Jewish organizations and local synagogues host communal Seders for those who cannot celebrate with family.

In the Diaspora, Pesach lasts eight days instead of seven, with two seders instead of one (the additional seder is held on the second night). Many Jews follow a wide variety of traditions based on their specific ethnic backgrounds (Ashkenazi, Sephardi, Mizrahi, etc.).

A unique tradition celebrated by North African Jewish communities on the day after Passover is the 'Mimouna,' featuring festive foods and welcoming guests.

If you are planning to visit Israel during the time of Pesach, you should definitely go to a Mimouna, since this is a lovely experience you definitely do not want to miss!

The Importance of Pesach for Believers in Yeshua

Pesach is a time of reflection and celebration of God’s faithfulness and redemption, and remains deeply relevant for all disciples of Yeshua and believers in the God of Israel. The Exodus narrative serves as a metaphor for personal and spiritual liberation, therefore it carries a profound theme of deliverance and freedom.

Pesach speaks volumes about covenant and commitment. It reminds of our covenant relationship with God and our responsibilities in faith.

Additionally, Pesach challenges us to grow in faith and trust. This holiday calls us to place our trust in our Father in Heaven, just like the children of Israel had to trust in God’s deliverance during the Exodus.

Pesach foreshadowed Yeshua’s redemptive work. These are the main points that connect all believers of all nations to Pesach:

- Yeshua is the Passover Lamb – The New Testament refers to Yeshua as "the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world" (John 1:29). His crucifixion coincided with the Passover sacrifice.

- The Last Supper was a Pesach Seder – It is believed that it was at this Seder where God, through Yeshua, inaugurated the New Covenant promised by the prophet Jeremiah.

- Redemption from Sin – Just as the children of Israel were redeemed from physical slavery, Yeshua’s sacrifice redeems believers from spiritual slavery to sin.

- The Blood of the Lamb – Just as the blood of the lamb marked the Israelites' homes to be 'passed over' from the death of the firstborn, Yeshua’s blood marks believers for salvation, so that they can be passed over from God's judgment.

To learn more about the Lamb of God click here.

To learn more about the Passover Seder click here.

In conclusion, from a spiritual perspective, Pesach is probably the most universal and important feast for all believers in the God of Israel and Yeshua the Messiah.

May this article inspire you to celebrate the feast of Pesach with renewed passion and meaning and bless your life and walk with our Father in Heaven.

Thank you so much for teaching about the Passover so concretely.

Shalom, you are very welcome!

Blessings